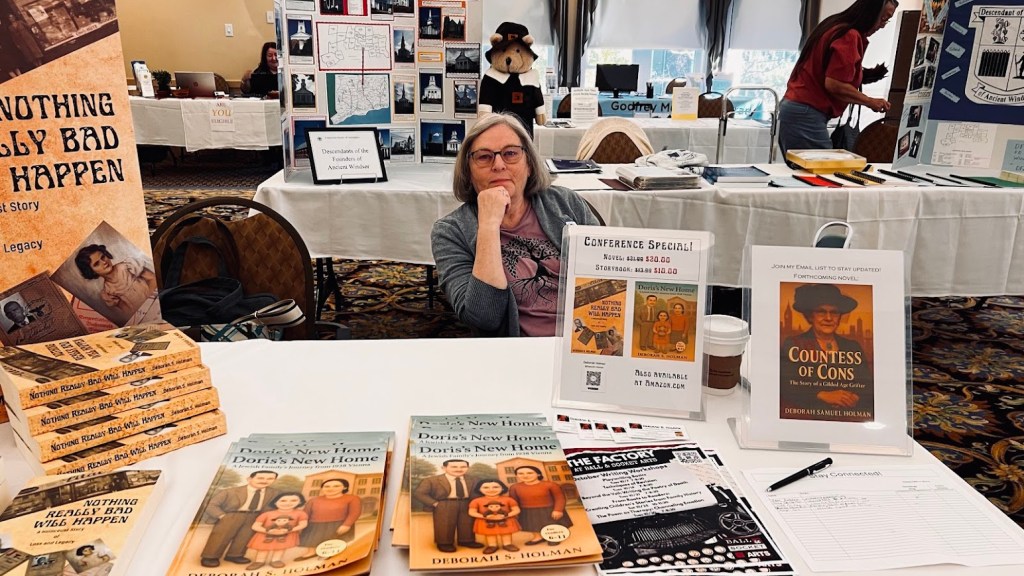

On Saturday, October 4, I had the pleasure of being a vendor at Family History Day, sponsored by the Connecticut Society of Genealogists. I always enjoy chatting with people who love family history, and inevitably, someone asks how I choose which ancestor to write about.

For my first novel, Nothing Really Bad Will Happen, the choice was clear. While helping my mother obtain reparations from the Austrian government in 2007, I uncovered a trove of documents detailing the trauma my family endured after losing their Viennese hat business in 1938.

That research opened my eyes to an overlooked part of Holocaust history. Most accounts focus on the years after 1941, but my family’s ordeal began in 1938, when my grandfather spent ten months in Dachau and Buchenwald. At that time, Jews were often arrested for their assets. It was essentially a ransom situation: pay a certain amount and agree to emigrate, and you’d be released from the camp. Simple—except that all your funds had already been frozen by the Nazis.

I don’t mean to minimize the horrors that followed once the “Final Solution” was put in place. But I felt it was important to shine a light on those early years of Nazi rule—when the machinery of persecution was already well underway, just in a different form. That’s how the novel was born.

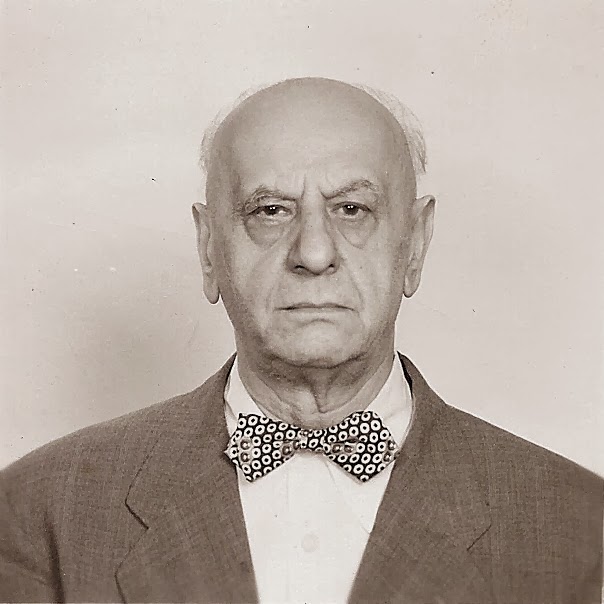

Through writing about my great-grandfather, Sigmund Lichtenthal, I began to understand why so many chose to stay. As Sigmund said, “Nothing really bad will happen. This has been happening to Jews for centuries.” I also came to see his personality more clearly: stern, stubborn, and at times, heartbreakingly cold.

My current project, Countess of Cons: The True Story of a Gilded-Age Grifter, explores my husband’s great-grandmother, Catherine C. Fitzallen, who turned to crime after her 1889 divorce from William A. Seeley. At first glance, Catherine appears unstable—perhaps even mentally ill. But as I uncovered newspaper articles detailing her often-hilarious escapades (and more than eighteen aliases!) and placed her life in the context of her times, I came to see her differently. She was a fiercely independent woman determined to live on her own terms—a nearly impossible feat in the 1890s, when women couldn’t vote, rarely owned property, and had little legal or financial autonomy. Thanks to Catherine’s resourcefulness, my husband’s family went on to prosper in Chicago well into the twentieth century.

Stories like Sigmund and Catherine’s remind me how vital context is in understanding the people who came before us. Once we learn what they were up against—the laws, the losses, the limited choices—their actions start to make sense in a way that transforms judgment into empathy.

That idea—the power of context to turn frustration into understanding—came up again and again at Family History Day. One conversation in particular stayed with me: a woman told me her father-in-law had been difficult his whole life—distant, rigid, hard to please. Only after learning what he had lived through did she finally understand him. Her story echoed so many others I’ve heard from genealogists who, through research, begin to see their ancestors in a new light. We all start out chasing facts—names, dates, records—but somewhere along the way, we start uncovering motives, fears, and resilience. And in doing so, we often learn a little more about ourselves.

Learning our ancestors’ stories helps us grasp not only who they were, but why they were that way. (It’s why I titled my blog Who We Are and How We Got This Way.)

Genealogy may start as a hobby, but family history is something deeper. It’s not just a collection of names, dates, and places—it’s a way to make sense of human experience across generations. When we study our ancestors’ lives, we’re not only preserving the past. We’re building compassion, context, and connection—qualities the world could use a little more of.

Be sure to subscribe to this blog as well as my author blog: deborahsholman.com in order to stay updated on the progress of the new novel!

Yes! Context is so vitally important and writing a novel (fictionalizing some aspects of real family history) gives the author freedom to explore that context, showing how it shaped and influenced the “characters” over time. Our characters in our family tree!

LikeLike

😍Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike